The VW-Rivian software deal and the future of the European automotive value network

VW admitted defeat and paid 6 billion US dollars for a 50% share in a joint venture that gives them access to Rivian's E/E architecture and software abstraction layer. It's a massive game changer.

Earlier this month, German car maker Volkswagen presented its newest EV model, the ID.1 (which will be the production grade car, but which was showcased as the ID.EVERY1, an 80% concept car version). It is supposed to be released in 2027. What is remarkable about this announcement is not so much the fact that VW aspires to make the ID.1 one of the first really affordable EVs in the mass market. It remains to be seen whether VW can a.) deliver on this promise and b.) on the promised timeline.

What’s remarkable though is that the 2nd biggest legacy car maker in the world finally gave up on its own software and E/E architecture attempts (despite trying hard) and fully adopted the approach of its joint venture partner Rivian, the Californian EV maker. From TechCrunch:

Volkswagen’s ultra-cheap EV called the ID EVERY1 — a small four-door hatchback revealed Wednesday — will be the first to roll out with software and architecture from Rivian, according to a source familiar with the new model.

Rivian’s Chief Software Officer Wassym Bensaid later confirmed the speculation in a posting on Linkedin:

He talks about the ID.1 being the first model to make use of Rivian’s full stack, but it seems like it’s not going to be the last one, according to VW. From AutoExpress:

Volkswagen’s board member for research and development, Kai Grunitz, told Auto Express: “First of all, it’s a flexible architecture, so I can change the scale [of the software system] – so I can just have one on something cost sensitive like ID.1, but then add more to more expensive models in the future. But it’s all the same software.

It is basically the story of operating systems: They can scale across different commoditized hardware architectures by integrating the hardware control capabilities into the software layer. We will dive into that topic later on. Two things stand out from that VW decision, from a strategy perspective - one that is explained best by the past of the industry and it’s structure and one that will predict its long-term future outlook. The fact that:

the entire approach of the German legacy industry to software and E/E, which had had its roots in the old value network logic, basically just collapsed with the VW announcement - and it was very obvious long ago that this would happen at some point

a key future value driver of the entire industry is now not designed and built anymore by the Germans, but is licensed from a Silicon Valley tech firm, which itself was partially acquired by VW through this Joint Venture (the other key value driver being battery design and production, which is a skill not mastered by Europeans either)

The software-defined car and software integration

So let’s start with the first one. What makes Rivian’s architecture special? I’m not going to do a deep dive into the details of software-defined architectures. I’m only going to give you the relevant high-level insights needed in order to understand the strategic implications of the ID.1 architecture, for the industry at large, and especially the German ecosystem of suppliers and OEMs. The following two interviews with Rivian’s Chief Software Officer Wassym Bensaid and with the Senior VP of Electrical Hardware Vidya Rajagopalan both shine light onto Rivian’s general approach in great detail, in case you’re interested.

Inside Rivian's Electrical Hardware Lab with Vidya Rajagopalan

Behind the Code: Rivian’s Software Updates with Wassym Bensaid

Here is only the kicker: It’s a full zonal architecture that was entirely designed and developed in-house, by Rivian’s software and hardware teams. Both the entire software stack, and the entire electronics and electrical architecture - including all zonal controllers, circuit boards, wiring layouts etc. It’s fully vertically integrated, with super short feedback loops when it comes to designing and testing changes and updates. There is no layered network of legacy automotive suppliers involved and hence no design-by-committee. The only noteworthy collaboration was the one directly with the leading chip manufacturers, namely Qualcomm and NVIDIA, when it came to circuit-board best practices, says Rajagopalan:

We obviously work with the chip suppliers, look at their reference designs and use them as a basis, but all our designs are uniquely ours, inhouse, done from scratch.

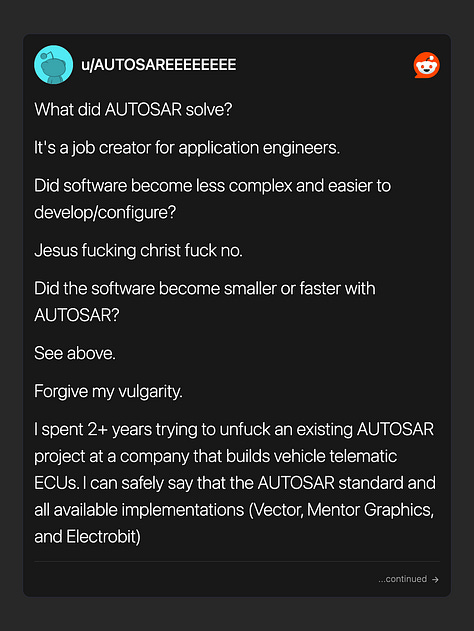

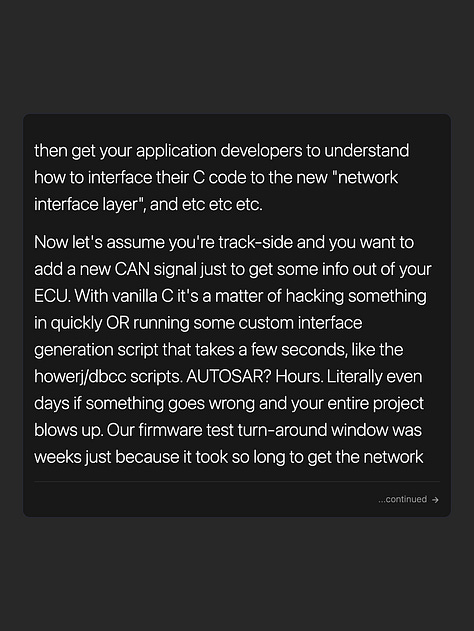

The most important thing that stands out from the software conversation is the fact that Rivian’s OS is not designed according to AUTOSAR standards, says Bensaid:

One of the intentional decisions that we have made is to not use AUTOSAR. You've probably heard about AUTOSAR, like in the traditional automotive world. Each of these pieces from the suppliers comes with, I'd say, excuse my word, an 'old school' operating system called AUTOSAR. It was created many, many years ago by a German consortium with the idea of having plug-and-play components. But then what they ended up doing is adding so much obfuscation in the software that it became really difficult to develop or to understand what's happening within the box.

The way we do things is: we love to see what's in the box; we love to develop the box; we love to optimize the box from the inside. We're always chasing waste in the box. So, what we have done is an intentional choice to not use AUTOSAR at all. And then, what we're using is our own operating system, which we call Safe RTOS, with hand-coded software. Our developers don't generate automated code like in the AUTOSAR world. Our developers hand-code the different functions so everything is optimized so that the system runs best together.

No AUTOSAR, no legacy supplier components, no legacy baggage. The fact that Rivian ditched AUTOSAR, and VW now fully adopts the Rivian approach, is much more than a technical decision. It is a classic story of disruptive business models at work - and a good example of how to avoid being trapped in old industry logic. So it might be the beginning of the end of an entire legacy value creation network that is centered around Germany and Western & Central Europe. In order to understand that, we need to understand what AUTOSAR is and how it came into being:

Legacy value networks, dominant industry logic and disruption

AUTOSAR is an embedded software standard framework developed from within the German industry, in 2003. Its development was driven by the critical need to standardize automotive software within a highly complex ecosystem. The German automotive landscape, characterized by a dense network of major Tier 1 suppliers and a vast array of Tier 2 and beyond, faced escalating software complexity as modern vehicles incorporated more and more Electronic Control Units (ECUs). It was supposed to provide a unified framework to ensure safety compliance and long-term maintainability while keeping costs under control through efficient software integration of different ECUs from different suppliers. So all the major OEMs and tier 1 suppliers came together back then and created a modular framework of rules and standards that describes how ECUs should be developed and how they should interact with each other - an 'old school' operating system, how Bensaid frames it today.

This is what they ended up with:

And here is why this is nowadays considered old school: Its complexity leads to a steep learning curve for developers, even for small tasks and projects. They have to learn how to use framework-specific development and testing tools before they even can start working on the problem. They also have to understand the framework as a whole, even when they only have to work on tiny elements of a whole system. This makes it expensive upfront (costs for tools and licensing, setup overhead, skills), debugging complicated and limits flexibility for customized solutions that don’t adhere to the standard. Since every module comes with certain layers of code that ensure overall compatibility, it introduces a problem that Bensaid called obfuscation: A lot of code (from the different standardized abstraction layers) needs to be processed by the microprocessor whether it adds value or not. This makes many processes computationally expensive and slow, and unnecessarily so.

If you ask developers themselves whether they like it or not, you will probably get mixed results. There is a now infamous Reddit post about its (mostly) cons and (not many) pros. Judge for yourself (and note the 2,5k likes in March 25):

I’m not going to judge whether the AUTOSAR approach was technically smart or not, back when it was conceived. It certainly goes against many modern software development practices. I want to highlight something else instead: From the business perspective of German auto managers, their approach was the obviously correct strategic approach! Here is why:

The industry was structured in a way that eventually benefited their best customers, who expected certain performance metrics (e.g., cost, quality, speed) - and safety was the most critical of those customer expectations (which in big companies often gets translated into ISO standards). So caution and perfection was valued above everything else in the industry - even when you design a software framework

A multi-layered supplier network was how cars were built back then. So of course those suppliers are the ones where you get your ECUs from. And in order to manage such an increasingly complex network, standardization made total sense. The idea of designing own systems-on-a-chip, together with chip manufacturers? Crazy! This was only 2 years after the dotcom bubble after all

Release cycles of 5-7 years for a new car model were the norm back then, so slow software development cycles were not a big issue in this world. The whole idea that car software would even change after the car had been sold to the customer was completely alien back then. So slow and steady perfection of all the software upfront was the obvious thing to do

All those obvious truths and the organizational processes aligned with them locked everyone in the industry into very similar, fine-tuned cost structures and profit margins. So the management incentives were very clear as well: That is the landscape in which they need to operate in, and they better not screw around with perfectly fine-tuned margins. So AUTOSAR was the solution to the perceived problem, given the existing reality and boundary conditions.

Enter the disruptive innovator: None of the above was true for Rivian. It did not build its software and E/E architecture from within the car industry, with the help of existing players, against existing constraints. It wasn’t incentivized to make decisions with a certain cost structure in mind. Rivian was founded in 2009. The EV value network was still brand new, and there was no traditional supplier base. Tesla had just released its first Roadster, and was in the middle of designing its first software-defined car, the Model S.

So Rivian started from scratch and massively tapped into the existing computer / software / consumer electronics industry value networks that are so prevalent in California (partnering with Qualcomm and NVIDIA, recruiting employees from Silicon Graphics, Google, Apples etc.). Here is how this made a difference in terms of priorities and procedures:

In this software world, short release cycles were the norm (several times per for for consumer software), so that is what was valued above everything else, historically (which is not to say that safety got deprioritized at Rivian)

A highly integrated approach of software and hardware was and is very common in Silicon Valley (Think Alan Kay, who inspired Steve Jobs: “People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware”)

Doing the development in-house and outsourcing manufacturing is a pretty common approach in the consumer electronics space (Think: Designed by Apple in California, made by Foxconn in Shenzhen, China)

Things like virtualization and cloud computing were already established in Silicon Valley since 2010 - just as the open-source ecosystem was alive and well there

It’s simply a different world with different views on how to do things. Innovation has almost nothing to do with the technology itself (especially in an R&D setup), or even with the product, and almost everything with processes, incentives and value networks at scale. It's nevertheless pretty questionable why most of the legacy industry still keeps on falling back to the AUTOSAR solution, since 1,5 decades, with minor adjustments - just because it is the thing to do that does not get you fired as an auto exec.

Platforms, modularization and the conservation of profits in the industry

Now that VW has basically given up on its own attempts of developing a hardware-software stack and will go with Rivian’s from here on, it seems clear that the software value network obviously became the dominant one. We can hence ask the question about the future of the industry as a whole: Is it really the beginning of the end of an entire legacy value creation network as I stated it above?

In order to predict that, one has to understand something that is called “The law of conservation of attractive profits”, formulated by Clayton Christensen. It is a central pillar in his industry disruption framework and when it comes to understanding how value is captured in an industry. It goes the following:

The law of conservation of attractive profits states that in the value chain there is a requisite juxtaposition of modular and interdependent architectures, and of reciprocal processes of commoditization and de-commoditisation, that exists in order to optimize the performance of what is not good enough. The law states that when modularity and commoditization cause attractive profits to disappear at one stage in the value chain, the opportunity to earn attractive profits with proprietary products will usually emerge at an adjacent stage.

Here is what that means, in simpler words:

In any given product architecture, there are parts that are necessary to make the product work, but not a differentiating factor, because their performance (be it speed or power) is already solved well enough from a customer point of view. Those bits and pieces are not what customers are paying for. They are commodities. They usually get outsourced once a way to integrate them into the whole system is found and well-specified. The integrator then can make suppliers bid against each other, and prices for the modules will go down - as do the profits for the suppliers.

Then there are other aspects of the product that are not solved well enough yet, from a customer perspective. That is what they actually pay money for. The company that can solve those problems the best (while constantly improving them), and that manages to integrate all the commoditized parts around it in a coherent product architecture, is the one that makes the most profits in the entire industry. It control the “not good enough” aspects customers are paying for, and can modularize everything else around it. That gives them economic power - as long as the performance of said aspect is still “not good enough”.

The Law now states that profits in a value chain are overall conserved - if they go away at one point due to commoditization, they appear somewhere else due to integration. It’s a back and forth within an industry, depending on the life cycle stage. And this where we can close the loop to VW jumping ship and going with Rivian’s architecture. In the new software and E/E world, many hardware components like electric motors, actuators or sensors (and even batteries) will become more and more commoditized, because they have become modularized.

Their capabilities are not determined anymore by (somewhat) complicated, and hence (somewhat) differentiated embedded software. Those embedded capabilities have been downgraded instead to simple on/off or move/stop-moving functions. Those are more or less trivial to make and are relatively easy to replicate, together with the actual hardware itself. They hence will become a commodity over time, as will their suppliers.

Meanwhile, the actual intelligence has moved somewhere else: The magic of future EV capabilities will be in the software control layer that orchestrates all the simplified hardware. What an EV can or can’t do will be determined by the zonal controllers (think drive train, autonomy, infotainment etc.) and by the central compute unit that orchestrates all the data. That capability is now what’s “not good enough yet”, what customers will pay money for - and hence the software layer is where most of the profits will be made in the industry. Just like in the PC industry in the 1980s, the magic is not in the hardware and peripherals anymore, but in the operating system that manages them all - just like when Microsoft came along and flipped the industry from a vertically integrated one to a modular one and became the dominant economic force for decades (together with Intel).

VW now admitted defeat on the OS battlefield and paid 6 billion US dollars for a 50% share in a joint venture that gives them access to this E/E architecture and its software abstraction layer. But note the following from the Rivian press release:

Teams will be based in Palo Alto, California initially, and three other sites are in development in North America and Europe.

The biggest German auto firm now deploys a platform into many if not all their future models that will commoditize most of the German supplier value network, and this platform layer skill will be first and foremost an American game, for the time being.

The future of the German auto industry - a dire outlook

To wrap it up, one can now tie the two concepts of value network structures and modularity vs. integration together, and it becomes easy to predict what is going to happen to the German auto industry:

The old logic of automotive suppliers delivering a somewhat differentiated component (due to embedded software) is gone - as will be most of their profits. Many if not most suppliers only function viably on top of a certain cost and margin structure. With those margins gone (because the products have been commoditized through software) the suppliers will not be able to operate economically anymore. They will need to downsize (potentially massively), or will go out of business, long term.

And since China is really far ahead when it comes to the electrical & electronics components supply chain at scale (+90% of all electronics devices worldwide are manufactured and assembled in and around Shenzhen), and is furthermore really good at automated manufacturing, it’s hard to see a future in which the automotive industry will continue to be centred around Western and Central Europe. The region simply won’t be competitive anymore, at least in a world without massive tariffs between the big economic zones. Especially Germany’s economic future is more dire than many people think.

Now that is all nice to understand in hindsight. Could legacy auto have done something differently, and earlier? I say yes: The entire logic of how disruptive innovations work has been well-described since decades. This is standard teaching material in all the relevant top MBA programs in the US. The automotive top management could and should have known earlier than 2024 that their path doomed to fail, due to all of the above mechanisms. This was not an unknown unknown.

But it is not for nothing that the sub title of Clayton Christensen's seminal book on technological disruption is When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. It’s simply hard for once successful incumbents to change from within, due to incentive structures - especially when they are focused on high-margin products for their best customers. Ford only abandoned all their legacy software and E/E approaches a few years ago (in 2022) and is now following Rivian’s vertically integrated, start-from-scratch path (in a completely independent business unit in California, far away from its HQ in Detroit). Its success remains to be seen. Rivian itself followed Tesla and BYD. The winning pattern therefore seems to be clear, just as the losing pattern seems to be clear as well by now. It will be interesting to see if and when players like BMW or Mercedes will follow - and whether the industry needs that many operating system platforms in the first place.

In any case, it is not a very comforting outlook for the legacy industry, and especially for Germany - with or without the ID.1 being actually available for 20.000 Euros in 2027.